Species of Thailand

Common buzzard

Buteo buteo

Carolus Linnaeus, 1758

In Thai: เหยี่ยวทะเลทรายตะวันตก

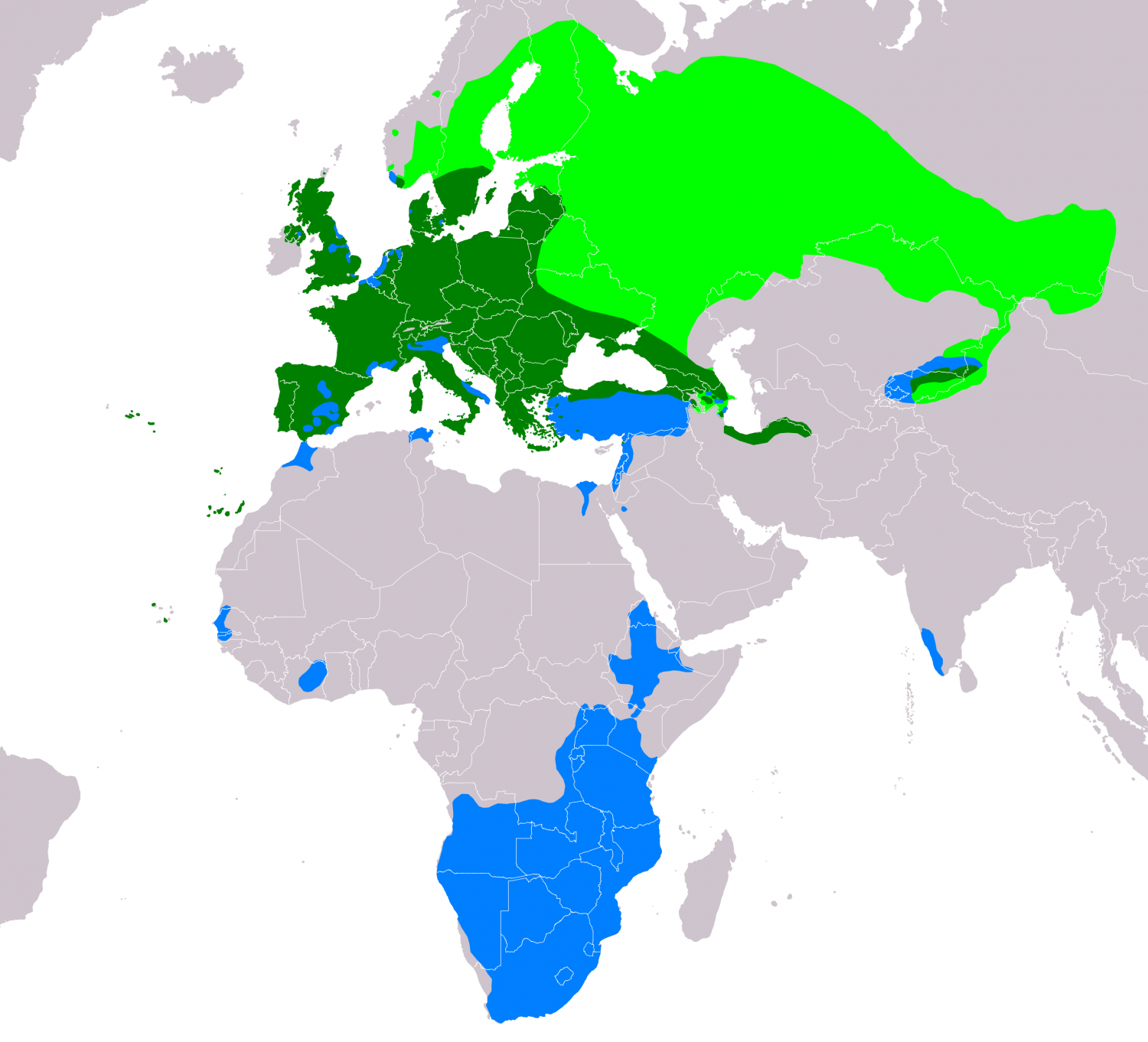

The common buzzard (Buteo buteo) is a medium-to-large bird of prey which has a large range. A member of the genus Buteo, it is a member of the family Accipitridae. The species lives in most of Europe and extends its breeding range across the Palearctic as far as the Russian Far East , northwestern China (Tien Shan) and northwestern Mongolia Over much of its range, it is a year-round resident. However, buzzards from the colder parts of the Northern Hemisphere as well as those that breed in the eastern part of their range typically migrate south for the northern winter, many culminating their journey as far as South Africa. The common buzzard is an opportunistic predator that can take a wide variety of prey, but it feeds mostly on small mammals, especially rodents such as voles. It typically hunts from a perch. Like most accipitrid birds of prey, it builds a nest, typically in trees in this species, and is a devoted parent to a relatively small brood of young. The common buzzard appears to be the most common diurnal raptor in Europe, as estimates of its total global population run well into the millions.

Taxonomy

The first formal description of the common buzzard was by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Falco buteo. The genus Buteo was introduced by the French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacépède in 1799 by tautonymy with the specific name of this species. The word buteo is Latin for a buzzard. It should not be confused with the Turkey vulture, which is sometimes called a buzzard in American English.

The Buteoninae subfamily originated from and is most diversified in the Americas, with occasional broader radiations that led to common buzzards and other Eurasian and African buzzards. The common buzzard is a member of the genus Buteo, a group of medium-sized raptors with robust bodies and broad wings. The Buteo species of Eurasia and Africa are usually commonly referred to as "buzzards" while those in the Americas are called hawks. Under current classification, the genus includes approximately 28 species, the second most diverse of all extant accipitrid genera behind only Accipiter. DNA testing shows that the common buzzard is fairly closely related to the red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) of North America, which occupies a similar ecological niche to the buzzard in that continent. The two species may belong to the same species complex. Two buzzards in Africa are likely closely related to the common buzzard based on genetic materials, the mountain (Buteo oreophilus) and forest buzzards (Buteo trizonatus), to the point where it has been questioned whether they are sufficiently distinct to qualify as full species. However, the distinctiveness of these African buzzards has generally been supported. Genetic studies have further indicated that the modern buzzards of Eurasia and Africa are a relatively young group, showing that they diverged at about 300, 000 years ago. Nonetheless, fossils dating earlier than 5 million year old (the late Miocene period) showed Buteo species were present in Europe much earlier than that would imply, although it cannot be stated to a certainty that these would’ve been related to the extant buzzards.

Subspecies and species splits

Some 16 subspecies have been described in the past and up to 11 are often considered valid, although some authorities accept as few as seven. Common buzzard subspecies fall into two groups.

The western buteo group is mainly resident or short-distance migrants and includes:

- B. b. buteo: Ranges in Europe from the Atlantic islands, the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula (including Madeira Island, whose population was once considered a separate race, B. b. harterti) more or less continuously throughout Europe to Finland, Romania and Asia Minor. This highly individually variable race is described below. This is a relatively large and bulky race of buzzard. In males, the wing chord ranges from 350 to 418 mm and the tail from 194 to 223 mm. In comparison, the larger female has a wing chord measuring 374 to 432 mm and tail length of 193 to 236 mm. In both sexes, the tarsus measures 69 to 83 mm in length. As illustrated by average body mass, sizes in the nominate race of common buzzard seem to confirm to Bergmann's rule, increasing to the north and decreasing closer to the Equator. In southern Norway, the mean weight of males was reportedly 740 g lb, while that of females was 1100 g lb. British buzzards were of intermediate size, 214 males averaging 781 g lb and 261 females averaging 969 g lb. Birds to the south in Spain were smaller, averaging 662 g lb in 22 males and 800 g lb in 30 females. Cramp and Simmons (1980) listed the mean body mass overall of nominate buzzards in Europe overall as 828 g lb in males and 1052 g lb in females.

- B. b. rothschildi: This proposed race is native to the Azores islands. It is generally considered a valid subspecies. This race differs from a typical intermediate of the nominate in being a darker, colder brown both above and below, closer to the darker individuals of the nominate. It averages smaller than most nominate buzzards. The wing chord of males ranges from 343 to 365 mm while that of females ranges from 362 to 393 mm.

- B. b. insularum: This race lives in the Canary Islands. Not all authorities consider this race suitably distinct, but others advocate it be retained as a full subspecies. It is typically of richer brown above and more heavily streaked below compared to nominate birds. It is similar in size to B. b. rothschildi and averages slightly smaller than the nominate race. Males have a reported wing chord of 352 to 390 mm and females have a wing chord of 370 to 394 mm.

- B. b. arrigonii: This race inhabits the islands of Corsica and Sardinia. It is generally considered a valid subspecies. The upper-side of these buzzards is an intermediate brown with very heavy streaking below, often covering the belly whereas most nominate buzzards show a whitish area the middle of the belly. Like most other insular races, this one is relatively small. Males possess a wing chord of 343 to 382 mm while females have a wing chord of 353 to 390 mm.

The eastern vulpinus group includes:

- B. b. vulpinus: The steppe buzzard breeds as far west as eastern Sweden, in the southern two-thirds of Finland, eastern Estonia, much of Belarus and the Ukraine, eastward to the northern Caucacus, northern Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, much of Russia to Altai and south-central Siberia, Tien Shan in China and western Mongolia. B. b. vulpinus is a long-distance migrant. It winters largely in much of eastern and southern Africa. Less frequently and often very discontinuously, steppe buzzards winter in the southern peninsulas of Europe, Arabia and southwestern India in addition to some parts of southeastern Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. In the open country favoured on the wintering grounds, steppe buzzards are often seen perched on roadside telephone poles. It at one time was considered a separate species due to differences in size, form, colouring and behaviour (especially in regards to migratory behaviour) but is genetically indistinct from nominate buzzards. Furthermore, the steppe buzzard engages in extensive interbreeding with the nominate race, mudding typical characteristics of both races. The zone of integration runs from Sweden and Finland through Eastern Europe, including any part of the overlapping ranges in the Baltic states, western Ukraine and eastern Romania. At times, the fertile hybrids of these two races have been erroneously proposed as races such as B. b. intermedius or B. b. zimmermannae. Intergrade buzzards are commonest where the grey-brown type of pale morphs of vulpinus are predominant. Steppe buzzards are usually distinctly smaller, with relatively longer wings and tail for their size, and thus often appear swifter and more agile in flight than nominate buzzards, whose wing beats can look slower and clumsier. Typically, their length is around 45 to 50 cm, while wingspan of males average 113 cm and females average 122.7 cm. The wing chord is 335 to 377 mm in males and 358 to 397 mm in females. Tail length is 170 to 200 mm in males and 175 to 209 mm in females. Weights of birds from Russia can reportedly range from 560 to 675 g lb in males and 710 to 1180 g lb in females. Weights of migrant birds appear to be lower than at other times of year for steppe buzzards. Two surveys of migrant buzzards during their huge spring movement in Eilat, Israel showed 420 birds averaged 579 g lb and 882 birds averaged 578 g lb. In comparison, weights of wintering steppe buzzards was higher, averaging 725 g lb in 35 birds in the former Transvaal (South Africa) and 739 g lb in 160 birds in the Cape Province. Weights of birds from Zambia were similar.

- B. b. menetriesi: This race is found in southern Crimea through the Caucasus to northern Iran and possibly into Turkey. This race has traditionally been listed as a resident race, but some sources consider it a migrant to eastern and southern Africa. Compared to the overlapping steppe buzzard subspecies, it is larger (roughly intermediate between the nominate race and vulpinus) and is duller in overall colour, being sandy below rather than rufous and lacking the bright rufous on the tail. Wing chord is 351 to 397 mm in males and 372 to 413 mm in females.

At one time, races of the common buzzard were thought to range as far in Asia as a breeding bird well into the Himalayas and as far east as northeastern China, Russia to the Sea of Okhotsk, and all the islands of the Kurile Islands and of Japan, despite both the Himalayan and eastern birds showing a natural gap in distribution from the next nearest breeding common buzzard. However, DNA testing has revealed that the buzzards of these populations probably belong to different species. Most authorities now accept these buzzards as full species: the eastern buzzard (Buteo japonicus; with three subspecies of its own) and the Himalayan buzzard (Buteo refectus). Buzzards found on the islands of Cape Verde off of the coast of western Africa, once referred to as the subspecies B. b. bannermani, and Socotra Island off of the northern peninsula of Arabia, once referred to as the rarely recognized subspecies B. b. socotrae, are now generally thought not to belong to the common buzzard. DNA testing has indicated that these insular buzzards are actually more closely related to the long-legged buzzard (Buteo rufinus) than to the common buzzard. Subsequently, some researchers have advocated full species status for the Cape Verde population, but the placement of these buzzards is generally deemed unclear.

Description

The common buzzard is a medium-sized raptor that is highly variable in plumage. Most buzzards are distinctly round headed with a somewhat slender bill, relatively long wings that either reach or fall slightly short of the tail tip when perched, a fairly short tail, and somewhat short and mainly bare tarsi. They can appear fairly compact in overall appearance but may also appear large relative to other commoner raptorial birds such as kestrels and sparrowhawks. The common buzzard measures between 40 and 58 cm in length with a 109 - 140 cm wingspan. Females average about 2–7% larger than males linearly and weigh about 15% more. Body mass can show considerable variation. Buzzards from Great Britain alone can vary from 427 to 1183 g lb in males, while females there can range from 486 to 1370 g lb.

In Europe, most typical buzzards are dark brown above and on the upperside of the head and mantle, but can become paler and warmer brown with worn plumage. The flight feathers on perched European buzzards are always brown in the nominate subspecies (B. b. buteo). Usually the tail will usually be narrowly barred grey-brown and dark brown with a pale tip and a broad dark subterminal band but the tail in palest birds can show a varying amount a white and reduced subterminal band or even appear almost all white. In European buzzards, the underside coloring can be variable but most typically show a brown-streaked white throat with a somewhat darker chest. A pale U across breast is often present; followed by a pale line running down the belly which separates the dark areas on breast-side and flanks. These pale areas tend to have highly variable markings that tend to form irregular bars. Juvenile buzzards are quite similar to adult in the nominate race, being best told apart by having a paler eye, a narrower subterminal band on the tail and underside markings that appear as streaks rather than bars. Furthermore, juveniles may show variable creamy to rufous fringes to upperwing coverts but these also may not be present. Seen from below in flight, buzzards in Europe typically have a dark trailing edge to the wings. If seen from above, one of the best marks is their broad dark subterminal tail band. Flight feathers of typical European buzzards are largely greyish, the aforementioned dark wing linings at front with contrasting paler band along the median coverts. In flight, paler individuals tend to show dark carpal patches that can appears as blackish arches or commas but these may be indistinct in darker individuals or can appear light brownish or faded in paler individuals. Juvenile nominate buzzards are best told apart from adults in flight by the lack of a distinct subterminal band (instead showing fairly even barring throughout) and below by having less sharp and brownish rather than blackish trailing wing edge. Juvenile buzzards show streaking paler parts of under wing and body showing rather than barring as do adults. Beyond the typical mid-range brownish buzzard, birds in Europe can range from almost uniform black-brown above to mainly white. Extreme dark individuals may range from chocolate brown to blackish with almost no pale showing but a variable, faded U on the breast and with or without faint lighter brown throat streaks. Extreme pale birds are largely whitish with variable widely spaced streaks or arrowheads of light brown about the mid-chest and flanks and may or may not show dark feather-centres on the head, wing-coverts and sometimes all but part of mantle. Individuals can show nearly endless variation of colours and hues in between these extremes and the common buzzard is counted among the most variably plumage diurnal raptors for this reason. One study showed that this variation may actually be the result of diminished single-locus genetic diversity.

Beyond the nominate form (B. b. buteo) that occupies most of the common buzzard's European range, a second main, widely distributed subspecies is known as the steppe buzzard (B. b. vulpinus). The steppe buzzard race shows three main colour morphs, each of which can be predominant in a region of breeding range. It is more distinctly polymorphic rather than just individually very variable like the nominate race. This may be because, unlike the nominate buzzard, the steppe buzzard is highly migratory. Polymorphism has been linked with migratory behaviour. The most common type of steppe buzzard is the rufous morph which gives this subspecies its scientific name (vulpes is Latin for "fox"). This morph comprises a majority of birds seen in passage east of the Mediterranean. Rufous morph buzzards are a paler grey-brown above than most nominate B. b. buteo. Compared to the nominate race, rufous vulpinus show a patterning not dissimilar but generally far more rufous-toned on head, the fringes to mantle wing coverts and, especially, on the tail and the underside. The head is grey-brown with rufous tinges usually while the tail is rufous and can vary from almost unmarked to thinly dark-barred with a subterminal band. The underside can be uniformly pale to dark rufous, barred heavily or lightly with rufous or with dusky barring, usually with darker individuals showing the U as in nominate but with a rufous hue. The pale morph of the steppe buzzard is commonest in the west of its subspecies range, predominantly seen in winter and migration at the various land bridge of the Mediterranean. As in the rufous morph, the pale morph vulpinus is grey-brown above but the tail is generally marked with thin dark bars and a subterminal band, only showing rufous near the tip. The underside in the pale morph is greyish-white with dark grey-brown or somewhat streaked head to chest and barred belly and chest, occasionally showing darker flanks that can be somewhat rufous. Dark morph vulpinus tend to be found in the east and southeast of the subspecies range and are easily outnumbered by rufous morph while largely using similar migration points. Dark morph individuals vary from grey-brown to much darker blackish-brown, and have a tail that is dark grey or somewhat mixed grey and rufous, is distinctly marked with dark barring and has a broad, black subterminal band. Dark morph vulpinus have a head and underside that is mostly uniform dark, from dark brown to blackish-brown to almost pure black. Rufous morph juveniles are often distinctly paler in ground colour (ranging even to creamy-grey) than adults with distinct barring below actually increased in pale morph type juvenile. Pale and rufous morph juveniles can only be distinguished from each other in extreme cases. Dark morph juveniles are more similar to adult dark morph vulpinus but often show a little whitish streaking below, and like all other races have lighter coloured eyes and more evenly barred tails than adults. Steppe buzzards tend to appear smaller and more agile in flight than nominate whose wing beats can look slower and clumsier. In flight, rufous morph vulpinus have their whole body and underwing varying from uniform to patterned rufous (if patterning present, it is variable, but can be on chest and often thighs, sometimes flanks, pale band across median coverts), while the under-tail usually paler rufous than above. Whitish flight feathers are more prominent than in nominate and more marked contrast with the bold dark brown band along the trailing edges. Markings of pale vulpinus as seen in flight are similar to rufous morph (such as paler wing markings) but more greyish both on wings and body. In dark morph vulpinus the broad black trailing edges and colour of body make whitish areas of inner wing stand out further with an often bolder and blacker carpal patch than in other morphs. As in nominate, juvenile vulpinus (rufous/pale) tend to have much less distinct trailing edges, general streaking on body and along median underwing coverts. Dark morph vulpinus resemble adult in flight more so than other morphs.

Similar species

The common buzzard is often confused with other raptors especially in flight or at a distance. Inexperienced and over-enthusiastic observers have even mistaken darker birds for the far larger and differently proportioned golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) and also dark birds for western marsh harrier (Circus aeruginosus) which also flies in a dihedral but is obviously relatively much longer and slenderer winged and tailed and with far different flying methods. Also buzzards may possibly be confused with dark or light morph booted eagles (Hieraeetus pennatus), which are similar in size, but the eagle flies on level, parallel-edged wings which usually appear broader, has a longer squarer tail, with no carpal patch in pale birds and all dark flight feathers but for whitish wedge on inner primaries in dark morph ones. Pale individuals are sometimes also mistaken with pale morph short-toed eagles (Circaetus gallicus) which are much larger with a considerably bigger head, longer wings (which are usually held evenly in flight rather than in a dihedral) and paler underwing lacking any carpal patch or dark wing lining. More serious identification concerns lie in other Buteo species and in flight with honey buzzards, which are quite different looking when seen perched at close range. The European honey buzzard (Pernis apivorus) is thought in engage in mimicry of more powerful raptors, in particular, juveniles may mimic the plumage of the more powerful common buzzard. While less individually variable in Europe, the honey buzzard is more extensive polymorphic on underparts than even the common buzzard. The most common morph of the adult European honey buzzard is heavily and rufous barred on the underside, quite different from the common buzzard, however the brownish juvenile much more resembles an intermediate common buzzard. Honey buzzards flap with distinctively slower and more even wing beats than common buzzard. The wings are also lifted higher on each upstroke, creating a more regular and mechanical effect, furthermore their wings are held slightly arched when soaring but not in a V. On the honey buzzard, the head appears smaller, the body thinner, the tail longer and the wings narrower and more parallel edged. The steppe buzzard race is particularly often mistaken for juvenile European honey buzzards, to the point where early observers of raptor migration in Israel considered distant individuals indistinguishable. However, when compared to a steppe buzzard, the honey buzzard has distinctly darker secondaries on the underwing with fewer and broader bars and more extensive black wing-tips (whole fingers) contrasting with a less extensively pale hand. Found in the same range as the steppe buzzard in some parts of southern Siberia as well as (with wintering steppes) in southwestern India, the Oriental honey buzzard (Pernis ptilorhynchus) is larger than both the European honey buzzard and the common buzzard. The oriental species is with more similar in body plan to common buzzards, being relatively broader winged, shorter tailed and more amply-headed (though the head is still relatively small) relative to the European honey buzzard, but all plumages lack carpal patches.

In much of Europe, the common buzzard is the only type of buzzard. However, the subarctic breeding rough-legged buzzard (Buteo lagopus) comes down to occupy much of the northern part of the continent during winter in the same haunts as the common buzzard. However, the rough-legged buzzard is typically larger and distinctly longer-winged with feathered legs, as well as having a white based tail with a broad subterminal band. Rough-legged buzzards have slower wing beats and hover far more frequently than do common buzzards. The carpal patch marking on the under-wing are also bolder and blacker on all paler forms of rough-legged hawk. Many pale morph rough-legged buzzards have a bold, blackish band across the belly against contrasting paler feathers, a feature which rarely appears in individual common buzzard. Usually the face also appears somewhat whitish in most pale morphs of rough-legged buzzards, which is true of only extremely pale common buzzards. Dark morph rough-legged buzzards are usually distinctly darker (ranging to almost blackish) than even extreme dark individuals of common buzzards in Europe and still have the distinct white-based tail and broad subterminal band of other roughlegs. In eastern Europe and much of the Asian range of common buzzards, the long-legged buzzard (Buteo rufinus) may live alongside the common species. As in the steppe buzzard race, the long-legged buzzard has three main colour morphs that are more or less similar in hue. In both the steppe buzzard race and long-legged buzzard, the main colour is overall fairly rufous. More so than steppe buzzards, long-legged buzzards tend to have a distinctly paler head and neck compared to other feathers, and, more distinctly, a normally unbarred tail. Furthermore, the long-legged buzzard is usually a rather larger bird, often considered fairly eagle-like in appearance (although it does appear gracile and small-billed even compared to smaller true eagles), an effect enhanced by its longer tarsi, somewhat longer neck and relatively elongated wings. The flight style of the latter species is deeper, slower and more aquiline, with much more frequent hovering, showing a more protruding head and a slightly higher V held in a soar. The smaller North African and Arabian race of long-legged buzzard (B. r. cirtensis) is more similar in size and nearly all colour characteristics to steppe buzzard, extending to the heavily streaked juvenile plumage, in some cases such birds can be distinguished only by their proportions and flight patterns which remain unchanged. Hybridization with the latter race (B. r. cirtensis) and nominate common buzzards has been observed in the Strait of Gibraltar, a few such birds have been reported potentially in the southern Mediterranean due to mutually encroaching ranges, which are blurring possibly due to climate change.

Wintering steppe buzzards may live alongside mountain buzzards and especially with forest buzzard while wintering in Africa. The juveniles of steppe and forest buzzards are more or less indistinguishable and only told apart by proportions and flight style, the latter species being smaller, more compact, having a smaller bill, shorter legs and shorter and thinner wings than a steppe buzzard. However, size is not diagnostic unless side by side as the two buzzards overlap in this regard. Most reliable are the species wing proportions and their flight actions. Forest buzzard have more flexible wing beats interspersed with glides, additionally soaring on flatter wings and apparently never engage in hovering. Adult forest buzzards compared to the typical adult steppe buzzard (rufous morph) are also similar, but the forest typically has a whiter underside, sometimes mostly plain white, usually with heavy blotches or drop-shaped marks on abdomen, with barring on thighs, more narrow tear-shaped on chest and more spotted on leading edges of underwing, usually lacking marking on the white U across chest (which is otherwise similar but usually broader than that of vulpinus). In comparison, the mountain buzzard, which is more similar in size to the steppe buzzard and slightly larger than the forest buzzard, is usually duller brown above than a steppe buzzard and is more whitish below with distinctive heavy brown blotches from breasts to the belly, flanks and wing linings while juvenile mountain buzzard is buffy below with smaller and streakier markings. The steppe buzzard when compared to another African species, the red-necked buzzard (Buteo auguralis), which has red tail similar to vulpinus, is distinct in all other plumage aspects despite their similar size. The latter buzzard has a streaky rufous head and is white below with a contrasting bold dark chest in adult plumage and, in juvenile plumage, has heavy, dark blotches on the chest and flanks with pale wing-linings. Jackal and augur buzzards (Buteo rufofuscus & augur), also both rufous on the tail, are larger and bulkier than steppe buzzards and have several distinctive plumage characteristics, most notably both having their own striking, contrasting patterns of black-brown, rufous and cream.

Distribution and habitat

The common buzzard is found throughout several islands in the eastern Atlantic islands, including the Canary Islands and Azores and almost throughout Europe. It is today found in Ireland and in nearly every part of Scotland and England. In mainland Europe, remarkably, there are no substantial gaps without breeding common buzzards from Portugal and Spain to Greece, Estonia, Belarus and the Ukraine, though are present mainly only in the breeding season in much of the eastern half of the latter three countries. They are also present in all larger Mediterranean islands such as Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily and Crete. Further north in Scandinavia, they are found mainly in southeastern Norway (though also some points in southwestern Norway close to the coast and one section north of Trondheim), just over the southern half of Sweden and hugging over the Gulf of Bothnia to Finland where they live as a breeding species over nearly two-thirds of the land. The common buzzard reaches its northern limits as a breeder in far eastern Finland and over the border to European Russia, continuing as a breeder over to the narrowest straits of the White Sea and nearly to the Kola Peninsula. In these northern quarters, the common buzzard is present typically only in summer but is a year-around resident of a hearty bit of southern Sweden and some of southern Norway. Outside of Europe, it is a resident of northern Turkey (largely close to the Black Sea) otherwise occurring mainly as a passage migrant or winter visitor in the remainder of Turkey, Georgia, sporadically but not rarely in Azerbaijan and Armenia, northern Iran (largely hugging the Caspian Sea) to northern Turkmenistan. Further north though its absent from either side of the northern Caspian Sea, the common buzzard is found in much of western Russia (though exclusively as a breeder) including all of the Central Federal District and the Volga Federal District, all but the northernmost parts of the Northwestern and Ural Federal Districts and nearly the southern half of the Siberian Federal District, its farthest easterly occurrence as a breeder. It also found in northern Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, far northwestern China (Tien Shan) and northwestern Mongolia. Non-breeding populations occur, either as migrants or wintering birds, in southwestern India, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt (northeastern), northern Tunisia (and far northwestern Algeria), northern Morocco, near the coasts of The Gambia, Senegal and far southwestern Mauritania and Ivory Coast (and bordering Burkina Faso). In eastern and central Africa, it is found in winter from southeastern Sudan, Eritrea, about two-thirds of Ethiopia, much of Kenya (though apparently absent from the northeast and northwest), Uganda, southern and eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, and more or less the entirety of southern Africa from Angola across to Tanzania down the remainder of the continent (but for an apparent gap along the coast from southwestern Angola to northwestern South Africa).

The common buzzard generally inhabits the interface of woodlands and open grounds; most typically the species lives in forest edge, small woods or shelterbelts with adjacent grassland, arables or other farmland. It acquits to open moorland as long as there is some trees. The woods they inhabit may be coniferous, temperate broad-leafed or mixed forests with occasional preferences for the local dominant tree. It is absent from treeless tundra and sporadic or rare in treeless steppe but can migrate through these, and may be found to some extent in both in mountainous or flat country. Buzzards in well-wooded areas of eastern Poland largely used large, mature stands of trees that were more humid, richer and denser than prevalent in surrounding area, but showed preference for those within 30 to 90 m of openings. Mostly resident buzzards live in lowlands and foothills, but they can live in timbered ridges and uplands as well as rocky coasts, sometimes nesting on cliff ledges rather than trees. Buzzards may live from sea level to elevations of 2000 m, breeding mostly below 1000 m but they can winter to an elevation of 2500 m and migrates easily to 4500 m. In the mountainous Italian Apennines, buzzard nests were at a mean elevation of 1399 m and were, relative to the surrounding area, further from human developed areas (i.e. roads) and nearer to valley bottoms in rugged, irregularly topographed places, especially ones that faced northeast. Common buzzards are fairly adaptable to agricultural lands but will show can show regional declines in apparent response to agriculture. Changes to more extensive agricultural practices were shown to reduce buzzard populations in western France where reduction of “hedgerows, woodlots and grasslands areas" caused a decline of buzzards and in Hampshire, England where more extensive grazing by free-range cattle and horses led to declines of buzzards, probably largely due to the seeming reduction of small mammal populations there. Similarly, urbanization seems to negatively affect buzzards, this species being generally less adaptable to urban areas than their New World counterparts, the red-tailed hawk. Although peri-urban areas can actually increase potential prey populations in a location, individual buzzard mortality, nest disturbances and nest habitat degradation rises significantly in such areas.

Behaviour

The common buzzard is a typical Buteo in much of its behaviour. It is most often seen either soaring at varying heights or perched on prominently on tree top, bare branch, telegraph pole, fence post, rock or ledge, or alternately well inside tree canopy. Buzzards will also stand and forage on the ground. In resident populations, it may spend more than half of its day inactively perched. Furthermore, it has been described a "sluggish and not very bold" bird of prey. It is a gifted soarer once aloft and can do so for extended periods but can appear laborious and heavy in level flight, more so nominate buzzards than steppe buzzards. Particularly in migration, as was recorded in the case of steppe buzzards' movement over Israel, buzzards readily adjust their direction, tail and wing placement and flying height to adjust for the surrounding environment and wind conditions. Israeli migrant buzzards rarely soar all that high (maximum 1000 - 2000 m above ground) due to the lack of mountain ridges that in other areas typically produce flyways; however tail-winds could be significant and this may allowed birds to cover a mean of 9.8 metres per second.

Migration

The common buzzard is aptly described as a partial migrant. The autumn and spring movements of buzzards are subject to extensive variation, even down to the individual level, based on a region's food resources, competition (both from other buzzards and other predators), extent of human disturbance and weather conditions. Short distance movements are the norm for juveniles and some adults in autumn and winter, but more adults in central Europe and the British Isles remain on their year-around residence than do not. Even for first year juvenile buzzards dispersal may not take them very far. In England, 96% of first-years moved in winter to less than 100 km from their natal site. Southwestern Poland was recorded to be a fairly important wintering grounds for central European buzzards in early spring that apparently travelled from somewhat farther north, in winter average density was a locally high 2.12 individual per square kilometer. Habitat and prey availability seemed to be the primary drivers of habitat selection in fall for European buzzards. In northern Germany, buzzards were recorded to show preferences in fall for areas fairly distant from nesting site, with a large quantity of vole-holes and more widely dispersed perches. In Bulgaria, the mean wintering density was 0.34 individual per square kilometer, and buzzards showed a preference for agricultural over forested areas. Similar habitat preferences were recorded in northeastern Romania, where buzzard density was 0.334–0.539 individuals per square kilometer. The nominate buzzards of Scandinavia are somewhat more strongly migratory than most central European populations. However, birds from Sweden show some variation in migratory behaviours. A maximum of 41, 000 individuals have been recorded at one of the main migration sites within southern Sweden in Falsterbo. In southern Sweden, winter movements and migration was studied via observation of buzzard colour. White individuals were substantially more common in southern Sweden rather than further north in their Swedish range. The southern population migrates earlier than intermediate to dark buzzards, in both adults and juveniles. A larger proportion of juveniles than of adults migrate in the southern population. Especially adults in the southern population are resident to a higher degree than more northerly breeders.

The behaviour of the steppe buzzard race differs, of course, as in no part of the range will this subspecies use the same summering and wintering grounds and the entire population is strongly migratory, covering substantial distances in these movements. Steppe buzzards are particularly prone to being slightly gregarious in migration, and will traveling in variously sized flocks. This race migrates in September to October often from Asia Minor to Cape of Africa in about a month but does not do well at crossing water, following around the Winam Gulf of Lake Victoria rather than crossing the several kilometer wide gulf. Similarly, they will funnel along both sides of the Black Sea. Migratory behavior of steppe buzzards mirrors those of broad-winged & Swainson's hawks (Buteo platypterus & swainsoni) in every significant way as similar long-distance migrating Buteos, including trans-equatorial movements, avoidance of large bodies of waters and flocking behaviour. Migrating steppe buzzards will rise up with the morning thermals and can cover an average of hundreds of miles a day using the available currents along mountain ridges and other topographic features. The spring migration for steppe buzzards peaks around March–April, but the latest vulpinus arrive in their breeding grounds by late April or early May. Distances covered by migrating steppe buzzards in one way flights from northern Europe (i.e. Finland or Sweden) to southern Africa have ranged over 13000 km within a season . For the steppe buzzards from eastern and northern Europe and western Russia (which compromise a majority of all steppe buzzards), peak migratory numbers occur in differing areas in autumn, when the largest recorded movements occurs through Asia Minor such as Turkey, than in spring, when the largest recorded movement are to the south in the Middle East, especially Israel. The two migratory movements barely differ overall until they reach the Middle East and east Africa, where the largest volume of migrants in autumn occurs at the southern part of the Red Sea, around Djibouti and Yemen, while the main volume in spring is in the northernmost strait, around Egypt and Israel. In autumn, numbers of steppe buzzards recorded in migration have ranged up to 32, 000 (recorded 1971) in northwestern Turkey (Bosporus) and in northeastern Turkey (Black Sea) up to 205, 000 (recorded 1976). Further down in migration, autumn numbers of up to 98, 000 have been recorded in passage in Djibouti. Between 150, 000 and nearly 466, 000 Steppe Buzzard have been recorded migrating through Israel during spring, making this not only the most abundant migratory raptor here but one of the largest raptor migrations anywhere in the world. Migratory movements of southern Africa buzzards largely occur along the major mountain ranges, such as the Drakensberg and Lebombo Mountains. Wintering steppe buzzards occur far more irregularly in Transvaal than Cape region in winter. The onset of migratory movement for steppe buzzards back to the breeding grounds in southern Africa is mainly in March, peaking in the second week. Steppe buzzard molt their feathers rapidly upon arrival at wintering grounds and seems to split their flight feather molt between breeding ground in Eurasia and wintering ground in southern Africa, the molt pausing during migration. In last 50 years, it was recorded that nominate buzzards are typically migrating shorter distances and wintering further north, possibly in response to climate change, resulting in relatively smaller numbers of them at migration sites. They are also extending their breeding range possibly reducing/supplanting steppe buzzards.

Vocalizations

Resident populations of common buzzards tend to vocalize all year around, whereas migrants tend to vocalize only during the breeding season. Both nominate buzzards and steppe buzzards (and their numerous related subspecies within their types) tend to have similar voices. The main call of the species is a plaintive, far-carrying pee-yow or peee-oo, used as both contact call and more excitedly in aerial displays. Their call is sharper, more ringing when used in aggression, tends to be more drawn-out and wavering when chasing intruders, sharper, more yelping when as warning when approaching the nest or shorter and more explosive when called in alarm. Other variations of their vocal performances include a cat-like mew, uttered repeatedly on the wing or when perched, especially in display; a repeated mah has been recorded as uttered by pairs answering each other, further chuckles and croaks have also been recorded at nests. Juveniles can usually be distinguished by the discordant nature of their calls compared to those of adults.

Dietary biology

The common buzzard is a generalist predator which hunts a wide variety of prey given the opportunity. Their prey spectrum extents to a wide variety of vertebrates including mammals, birds (from any age from eggs to adult birds), reptiles, amphibians and, rarely, fish, as well as to various invertebrates, mostly insects. Young animals are often attacked, largely the nidifugous young of various vertebrates. In total well over 300 prey species are known to be taken by common buzzards. Furthermore, prey size can vary from tiny beetles, caterpillars and ants to large adult grouse and rabbits up to nearly twice their body mass. Mean body mass of vertebrate prey was estimated at 179.6 g in Belarus. At times, they will also subsist partially on carrion, usually of dead mammals or fish. However, dietary studies have shown that they mostly prey upon small mammals, largely small rodents. Like many temperate zone raptorial birds of varied lineages, voles are an essential part of the common buzzard's diet. This bird's preference for the interface between woods and open areas frequently puts them in ideal vole habitat. Hunting in relatively open areas has been found to increase hunting success whereas more complete shrub cover lowered success. A majority of prey is taken by dropping from perch, and is normally taken on ground. Alternately, prey may be hunted in a low flight. This species tends not to hunt in a spectacular stoop but generally drops gently then gradually accelerate at bottom with wings held above the back. Sometimes, the buzzard also forages by random glides or soars over open country, wood edges or clearings. Perch hunting may be done preferentially but buzzards fairly regularly also hunt from a ground position when the habitat demands it. Outside the breeding season, as many 15–30 buzzards have been recorded foraging on ground in a single large field, especially juveniles. Normally the rarest foraging type is hovering. A study from Great Britain indicated that hovering does not seem to increase hunting success.

Mammals

A high diversity of rodents may be taken given the chance, as around 60 species of rodent have been recorded in the foods of common buzzards. It seems clear that voles are the most significant prey type for European buzzards. Nearly every study from the continent makes reference to the importance, in particular, of the two most numerous and widely distributed European voles: the 28.5 g common vole (Microtus arvalis) and the somewhat more northerly ranging 40 g field vole (Microtus agrestis). In southern Scotland, field voles were the best represented species in pellets, accounting for 32.1% of 581 pellets. In southern Norway, field voles were again the main food in years with peak vole numbers, accounting for 40.8% of 179 prey items in 1985 and 24.7% of 332 prey items in 1994. Altogether, rodents amount to 67.6% and 58.4% of the foods in these respective peak vole years. However, in low vole population years, the contribution of rodents to the diet was minor. As far west as the Netherlands, common voles were the most regular prey, amounting to 19.6% of 6624 prey items in a very large study. Common voles were the main foods recorded in central Slovakia, accounting for 26.5% of 606 prey items. The common vole, or other related vole species at times, were the main foods as well in the Ukraine (17.2% of 146 prey items) ranging east to Russia in the Privolshky Steppe Nature Reserve (41.8% of 74 prey items) and in Samara (21.4% of 183 prey items). Other records from Russia and the Ukraine show voles ranging from slightly secondary prey to as much as 42.2% of the diet. In Belarus, voles, including Microtus species and 18.4 g bank voles (Myodes glareolus), accounted for 34.8% of the biomass on average in 1065 prey items from different study areas over 4 years. At least 12 species of the genus Microtus are known to be hunted by common buzzards and even this is probably conservative, moreover similar species like lemmings will be taken if available.

Other rodents are taken largely opportunistically rather than by preference. Several wood mice (Apodemus ssp.) are known to be taken quite frequently but given their preference for activity in deeper woods than the field-forest interfaces preferred, they are rarely more than secondary food items. An exception was in Samara where the yellow-necked mouse (Apodemus flavicollis), one of the largest of its genus at 28.4 g, made up 20.9%, putting it just behind the common vole in importance. Similarly, tree squirrels are readily taken but rarely important in the foods of buzzards in Europe, as buzzards apparently prefer to avoid taking prey from trees nor do they possess the agility typically necessary to capture significant quantities of tree squirrels. All four ground squirrels that range (mostly) into eastern Europe are also known to be common buzzard prey but little quantitative analysis has gone into how significant such predator-prey relations are. Rodent prey taken have ranged in size from the 7.8 g Eurasian harvest mouse (Micromys minutus) to the non-native, 1100 g lb muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus). Other rodents taken either seldomly or in areas where the food habits of buzzards are spottily known include flying squirrels, marmots (presumably very young if taken alive), chipmunks, spiny rats, hamsters, mole-rats, gerbils, jirds and jerboas and occasionally hearty numbers of dormice, although these are nocturnal. Surprisingly little research has gone into the diets of wintering steppe buzzards in southern Africa, considering their numerous status there. However, it has been indicated that the main prey remains consist of rodents such as the four-striped grass mouse (Rhabdomys pumilio) and Cape mole-rats (Georychus capensis).

Other than rodents, two other groups of mammals can be counted as significant to the diet of common buzzards. One of these main prey type of import in the diets of common buzzards are leporids or lagomorphs, especially the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) where it is found in numbers in a wild or feral state. In all dietary studies from Scotland, rabbits were highly important to the buzzard's diet. In southern Scotland, rabbits constituted 40.8% of remains at nests and 21.6% of pellet contents, while lagomorphs (mainly rabbits but also some young hares) were present in 99% of remains in Moray, Scotland. The nutritional richness relative to the commonest prey elsewhere, such as voles, might account for the high productivity of buzzards here. For example, clutch sizes were twice as large on average where rabbits were common (Moray) than were where they were rare (Glen Urquhart). In northern Ireland, an area of interest because it is devoid of any native vole species, rabbits were again the main prey. Here, lagomorphs constituted 22.5% of prey items by number and 43.7% by biomass. While rabbits are non-native, albeit long-established, in the British Isles, in their native area of the Iberian peninsula, rabbits are similarly significant to the buzzard's diet. In Murcia, Spain, rabbits were the most common mammal in the diet, making up 16.8% of 167 prey items. In a large study from northeastern Spain, rabbits were dominant in the buzzard's foods, making up 66.5% of 598 prey items. In the Netherlands, European rabbits were second in number (19.1% of 6624 prey items) only to common voles and the largest contributor of biomass to nests (36.7%). Outside of these (at least historically) rabbit-rich areas, leverets of the common hare species found in Europe can be important supplemental prey. European hare (Lepus europaeus) were the fourth most important prey species in central Poland and the third most significant prey species in Stavropol Krai, Russia. Buzzards normally attack the young of European rabbits, which as adults can average nearly 2000 g lb, and invariably (so far as is known) only the young of hares, which can average up to twice as massive as rabbits. The mean weights of rabbits taken have various been estimated from 159 to 550 g in different areas while mountain hares (Lepus timidus) taken in Norway were estimated to average about 1000 g lb, in both cases about a third of the weight of full-grown, prime adults of the respective species. However, hares and rabbits taken by female buzzards can infrequently include specimens that weigh up to 1600 g lb, including at times adult rabbits.

The other significant mammalian prey type is insectivores, among which more than 20 species are known to be taken by this species, including nearly all the species of shrew, mole and hedgehog found in Europe. Moles are taken particularly often among this order, since as is the case with "vole-holes", buzzard probably tend to watch molehills in fields for activity and dive quickly from their perch when one of the subterranean mammals pops up. The most widely found mole in the buzzard's northern range is the 98 g European mole (Talpa europaea) and this is one of the more important non-rodent prey items for the species. This species was present in 55% of 101 remains in Glen Urquhart, Scotland and was the second most common prey species (18.6%) in 606 prey items in Slovakia. In Bari, Italy, the Roman mole (Talpa romana), of similar size to the European species, was the leading identified mammalian prey, making up 10.7% of the diet. The full size range of insectivores may be taken by buzzards, ranging from the world's smallest mammal (by weight), the 1.8 g Etruscan shrew (Suncus etruscus) to arguably the heaviest insectivore, the 800 g European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus). Mammalian prey for common buzzards other than rodents, insectivores and lagomorphs is rarely taken. Occasionally, some weasels (including polecats) and perhaps martens might be attacked by buzzards, more likely the more powerful female buzzard since such prey is potentially dangerous and of similar size to a buzzard itself. Numerous larger mammals, including medium-sized carnivores such as dogs, cats and foxes and various ungulates, are sometimes eaten as carrion by buzzards, mainly during lean winter months. Still-borns of deer are also visited with some frequency.

Birds

When attacking birds, common buzzards chiefly prey on nestlings and fledglings of small to medium-sized birds, largely passerines but also a variety of gamebirds, but sometimes also injured, sickly or unwary but healthy adults. While capable of overpowering birds larger than itself, the common buzzard is usually considered to lack the agility necessary to capture many adult birds, even gamebirds which would presumably be weaker fliers considering their relatively heavy bodies and small wings. The amount of fledgling and younger birds preyed upon relative to adults is variable, however. For example, in the Italian Alps, 72% of birds taken were fledglings or recently fledged juveniles, 19% were nestlings and 8% were adults. On the contrary, in southern Scotland, even though the buzzards were taking relatively large bird prey, largely red grouse (Lagopus lagopus scotica), 87% of birds taken were reportedly adults. In total, as in many raptorial birds that are far from bird-hunting specialists, birds are the most diverse group in the buzzard's prey spectrum due to the sheer number and diversity of birds, few raptors do not hunt them at least occasionally. Nearly 150 species of bird have been identified in the common buzzard's diet. In general, despite many that are taken, birds usually take a secondary position in the diet after mammals. In northern Scotland, birds were fairly numerous in the foods of buzzards. The most often recorded avian prey and 2nd and 3rd most frequent prey species (after only field voles) in Glen Urquhart, were 23.9 g chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs) and 18.4 g meadow pipits (Anthus pratensis), with the buzzards taking 195 fledglings of these species against only 90 adults. This differed from Moray where the most frequent avian prey and 2nd most frequent prey species behind the rabbit was the 480 g common wood pigeon (Columba palumbus) and the buzzards took four times as many adults relative to fledglings.

Birds were the primary food for common buzzards in the Italian Alps, where they made up 46% of the diet against mammal which accounted for 29% in 146 prey items. The leading prey species here were 103 g Eurasian blackbirds (Turdus merula) and 160 g Eurasian jays (Garrulus glandarius), albeit largely fledglings were taken of both. Birds could also take the leading position in years with low vole populations in southern Norway, in particular thrushes, namely the blackbird, the 67.7 g song thrush (Turdus philomelos) and the 61 g redwing (Turdus iliacus), which were collectively 22.1% of 244 prey items in 1993. In southern Spain, birds were equal in number to mammals in the diet, both at 38.3%, but most remains were classified as "unidentified medium-sized birds", although the most often identified species of those that apparently could be determined were Eurasian jays and red-legged partridges (Alectoris rufa). Similarly, in northern Ireland, birds were roughly equal in import to mammals but most were unidentified corvids. In Seversky Donets, Ukraine, birds and mammals both made up 39.3% of the foods of buzzards. Common buzzards may hunt nearly 80 species passerines and nearly all available gamebirds. Like many other largish raptors, gamebirds are attractive to hunt for buzzards due to their ground-dwelling habits. Buzzards were the most frequent predator in a study of juvenile pheasants in England, accounting for 4.3% of 725 deaths (against 3.2% by foxes, 0.7% by owls and 0.5% by other mammals). They also prey on a wide size range of birds, ranging down to Europe's smallest bird, the 5.2 g goldcrest (Regulus regulus). Very few individual birds hunted by buzzards weigh more than 500 g lb. However, there have been some particularly large avian kills by buzzards, including any that weigh more or 1000 g lb, or about the largest average size of a buzzard, have including adults of mallard (Anas platyrhynchos), black grouse (Tetrao tetrix), ring-necked pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), common raven (Corvus corax) and some of the larger gulls if ambushed on their nests. The largest avian kill by a buzzard, and possibly largest known overall for the species, was an adult female western capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) that weighed an estimated 1985 g lb. At times, buzzards will hunt the young of large birds such as herons and cranes. Other assorted avian prey has included a few species of waterfowl, most available pigeons and doves, cuckoos, swifts, grebes, rails, nearly 20 assorted shorebirds, tubenoses, hoopoes, bee-eaters and several types of woodpecker. Birds with more conspicuous or open nesting areas or habits are more likely to have fledglings or nestlings attacked, such as water birds, while those with more secluded or inaccessible nests, such as pigeons/doves and woodpeckers, adults are more likely to be hunted.

Reptiles and amphibians

The common buzzard may be the most regular avian predator of reptiles and amphibians in Europe apart from the sections where they are sympatric with the largely snake-eating short-toed eagle. In total, the prey spectrum of common buzzards include nearly 50 herpetological prey species. In studies from northern and southern Spain, the leading prey numerically were both reptilian, although in Biscay (northern Spain) the leading prey (19%) was classified as "unidentified snakes". In Murcia, the most numerous prey was the 77.2 g ocellated lizard (Timon lepidus), at 32.9%. In total, at Biscay and Murcia, reptiles accounted for 30.4% and 35.9% of the prey items, respectively. Findings were similar in a separate study from northeastern Spain, where reptiles amounted to 35.9% of prey. In Bari, Italy, reptiles were the main prey, making up almost exactly half of the biomass, led by the large green whip snake (Hierophis viridiflavus), maximum size up to 1360 g lb, at 24.2% of food mass. In Stavropol Krai, Russia, the 20 g sand lizard (Lacerta agilis) was the main prey at 23.7% of 55 prey items. The 16 g slowworm (Anguis fragilis), a legless lizard, became the most numerous prey for the buzzards of southern Norway in low vole years, amounting to 21.3% of 244 prey items in 1993 and were also common even in the peak vole year of 1994 (19% of 332 prey items). More or less any snake in Europe is potential prey and the buzzard has been known to be uncharacteristically bold in going after and overpowering large snakes such as rat snakes, ranging up to nearly 1.5 m in length, and healthy, large vipers despite the danger of being struck by such prey. However, in at least one case, the corpse of a female buzzard was found envenomed over the body of an adder that it had killed. In some parts of range, the common buzzard acquires the habit of taking many frogs and toads. This was the case in the Mogilev Region of Belarus where the 23 g moor frog (Rana arvalis) was the major prey (28.5%) over several years, followed by other frogs and toads amounting to 39.4% of the diet over the years. In central Scotland, the 46 g common toad (Bufo bufo) was the most numerous prey species, accounting for 21.7% of 263 prey items, while the common frog (Rana temporaria) made up a further 14.7% of the diet. Frogs made up about 10% of the diet in central Poland as well.

Invertebrates and other prey

When common buzzards feed on invertebrates, these are chiefly earthworms, beetles and caterpillars in Europe and largely seemed to be preyed on by juvenile buzzards with less refined hunting skills or in areas with mild winters and ample swarming or social insects. In most dietary studies, invertebrates are at best a minor supplemental contributor to the buzzard's diet. Nonetheless, roughly a dozen beetle species have found in the foods of buzzards from the Ukraine alone. In winter in northeastern Spain, it was found that the buzzards switched largely from the vertebrate prey typically taken during spring and summer to a largely insect-based diet. Most of this prey was unidentified but the most frequently identified were European mantis (Mantis religiosa) and European mole cricket (Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa). In the Ukraine, 30.8% of the food by number was found to be insects. Especially in winter quarters such as southern Africa, common buzzards are often attracted to swarming locusts and other orthopterans. In this way the steppe buzzard may mirror a similar long-distance migrant from the Americas, the Swainson's hawk, which feeds its young largely on nutritious vertebrates but switches to a largely insect-based once the reach their distant wintering grounds in South America. In Eritea, 18 returning migrant steppe buzzards were seen to feed together on swarms of grasshoppers. For wintering steppe buzzards in Zimbabwe, one source went so far as to refer to them as primarily insectivorous, apparently being somewhat locally specialized to feeding on termites. Stomach contents in buzzards from Malawi apparently consisted largely of grasshoppers (alternately with lizards). Fish tend to be the rarest class of prey found in the common buzzard's foods. There are a couple cases of predation of fish detected in the Netherlands, while elsewhere they've been known to have fed upon eels and carp.

Interspecies predatory relationships

Common buzzards co-occur with dozens of other raptorial birds through their breeding, resident and wintering grounds. There may be many other birds that broadly overlap in prey selection to some extent. Furthermore, their preference for interferences of forest and field is used heavily by many birds of prey. Some of the most similar species by diet are the common kestrel (Falco tinniculus), hen harrier (Circus cyaenus) and lesser spotted eagle (Clanga clanga), not to mention nearly every European species of owl, as all but two may locally prefer rodents such as voles in their diets. Diet overlap was found to be extensive between buzzards and red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Poland, with 61.9% of prey selection overlapping by species although the dietary breadth of the fox was broader and more opportunistic. Both fox dens and buzzard roosts were found to be significantly closer to high vole areas relative to the overall environment here. The only other widely found European Buteo, the rough-legged buzzard, comes to winter extensively with common buzzards. It was found in southern Sweden, habitat, hunting and prey selection often overlapped considerably. Rough-legged buzzards appear to prefer slightly more open habitat and took slightly fewer wood mice than common buzzard. Roughlegs also hover much more frequently and are more given to hunting in high winds. The two buzzards are aggressive towards one another and excluded each other from winter feeding territories in similar ways to the way they exclude conspecifics. In northern Germany, the buffer of their habitat preferences apparently accounted for the lack of effect on each other's occupancy between the two buzzard species. Despite a broad range of overlap, very little is known about the ecology of common and long-legged buzzards where they co-exist. However, it can be inferred from the long-legged species preference for predation on differing prey, such as blind mole-rats, ground squirrels, hamsters and gerbils, from the voles usually preferred by the common species, that serious competition for food is unlikely.

A more direct negative effect has been found in buzzard's co-existence with northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis). Despite the considerable discrepancy of the two species dietary habits, habitat selection in Europe is largely similar between buzzards and goshawks. Goshawks are slightly larger than buzzards and are more powerful, agile and generally more aggressive birds, and so they are considered dominant. In studies from Germany and Sweden, buzzards were found to be less disturbance sensitive than goshawks but were probably displaced into inferior nesting spots by the dominant goshawks. The exposure of buzzards to a dummy goshawk was found to decrease breeding success whereas there was no effect on breeding goshawks when they were exposed to a dummy buzzard. In many cases, in Germany and Sweden, goshawks displaced buzzards from their nests to take them over for themselves. In Poland, buzzards productivity was correlated to prey population variations, particularly voles which could vary from 10–80 per hectare, whereas goshawks were seemingly unaffected by prey variations; buzzards were found here to number 1.73 pair per 10 sqkm against goshawk 1.63 pair per 10 sqkm. In contrast, the slightly larger counterpart of buzzards in North America, the red-tailed hawk (which is also slightly larger than American goshawks, the latter averaging smaller than European ones) are more similar in diet to goshawks there. Redtails are not invariably dominated by goshawks and are frequently able to outcompete them by virtue of greater dietary and habitat flexibility. Furthermore, red-tailed hawks are apparently equally capable of killing goshawks as goshawks are of killing them (killings are more one-sided in buzzard-goshawk interactions in favour of the latter). Other raptorial birds, including many of similar or mildly larger size than common buzzards themselves, may dominate or displace the buzzard, especially with aims to take over their nests. Species such as the black kite (Milvus migrans), booted eagle (Hieraeetus pennatus) and the lesser spotted eagle have been known to displace actively nesting buzzards, although in some cases the buzzards may attempt to defend themselves. The broad range of accipitrids that take over buzzard nests is somewhat unusual. More typically, common buzzards are victims of nest parasitism to owls and falcons, as neither of these other kinds of raptorial birds builds their own nests, but these may regularly take up occupancy on already abandoned or alternate nests rather than ones the buzzards are actively using. Even with birds not traditionally considered raptorial, such as common ravens, may compete for nesting sites with buzzards. Despite often being dominated in nesting site confrontations by even similarly s

This article uses material from Wikipedia released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike Licence 3.0. Eventual photos shown in this page may or may not be from Wikipedia, please see the license details for photos in photo by-lines.

Category / Seasonal Status

BCST Category: Recorded in an apparently wild state within the last 50 years

BCST Seasonal status: Non-breeding visitor

Scientific classification

- Kingdom

- Animalia

- Phylum

- Chordata

- Class

- Aves

- Order

- Accipitriformes

- Family

- Accipitridae

- Genus

- Buteo

- Species

- Buteo buteo

Common names

- Thai: เหยี่ยวทะเลทรายตะวันตก

Subspecies

Buteo buteo arrigonii, Signora Cecilia Picchi, 1903

Range: Corsica and Sardinia

Buteo buteo burmanicus, Allan Octavian Hume, 1875

Common name: Himalayan buzzard

Range: Himalayas and western China

Buteo buteo buteo, Carolus Linnaeus, 1758

Range: Most of Europe

Buteo buteo harterti, Henry Kirke Swann, 1919

Range: Madeira, doubtfully distinct from nominate buteo

Buteo buteo insularum, Curt Ehrenreich Flöricke, 1903

Range: Canary Islands

Buteo buteo japonicus, Carolus Linnaeus, 1758

Range: Japan: resident

Buteo buteo menetriesi, Modest Nikolajevitsh Bogdanov, 1879

Range: Caucasus

Buteo buteo oshiroi, Nagamichi Kuroda, 1971

Range: Daito Islands

Buteo buteo rothschildi, Henry Kirke Swann, 1919

Range: Azores

Buteo buteo toyoshimai, Tadashi Suzuki & Yuka Kato, 2005

Range: Izu Islands and Bonin Islands

Buteo buteo vulpinus, Constantin Wilhelm Lambert Gloger, 1833

Common name: Steppe buzzard

Range: Eurasia: migrant breeder

Conservation status

Least Concern (IUCN3.1)

Photos

Please help us review the bird photos if wrong ones are used. We can be reached via our contact us page.

Range Map

- Bang Saphan Noi District, Prachuap Khiri Khan

- Chiang Dao District, Chiang Mai

- Chiang Dao Wildlife Sanctuary

- Chiang Saen District, Chiang Rai

- Doi Inthanon National Park

- Doi Lo District, Chiang Mai

- Doi Pha Hom Pok National Park

- Doi Suthep - Pui National Park

- Fang District, Chiang Mai

- Hala-Bala Wildlife Sanctuary

- Khao Dinsor (Chumphon Raptor Center)

- Khao Sam Roi Yot National Park

- Khao Yai National Park

- Khun Tan District, Chiang Rai

- Lam Nam Kok National Park

- Mae Ai District, Chiang Mai

- Mae Fa Luang District, Chiang Rai

- Mae Taeng District, Chiang Mai

- Mueang Chiang Mai District, Chiang Mai

- Nong Bong Khai Non-Hunting Area